Roseau, Dominica, West Indies - March 1956

“I wonder how the English will respond to you, Tio.”

“What do you mean, Clara?”

“I mean, they have very different ways there. If you say things like you say them here, it may cause a commotion.”

“Like what?”

“Well, take for instance how you become vexed whenever you travel somewhere new. You won’t be able to do that there. You will have one of those police officers wearing a big pointed hat come and tell you to be quiet.”

“I don’t know where you get all of these things from. How often do you see me in trouble with the police here?”

“I am just teasing you, Tio.”

Both laughed at the thought of Tio being accosted by the police because of his ill humour. Then they were lost in their own thoughts once more.

Seated in a small patch of land adjacent Clara’s property, Tio had determined to clear as much hard manual work as possible for her before leaving. Soon, he would no longer be on hand to do such work. She and her mother would have to do it from now on. For the rest, she would have to pay someone.

Tio sat a short distance away from Clara upon a small tree stump, machete in hand, stripping husks from a dozen or so coconuts in a pile.

“Do you think the English are so different to us, Clara?”

She detected uncertainty in his voice. He was normally quite opinionated about matters such as this. Perhaps he was having second thoughts. She paused in contemplation before speaking.

“I think if you were to ask many people around here, they will tell you the same thing – the ones that come here look down on us.”

“But I’m not asking many people, Clara I’m asking you.”

“I used to know this English Creole girl when I was staying in Roseau with my aunt. She lived a street away in Goodwill, but in a much bigger and nicer house than ours. She would stare at me, I would stare at her. I would see her the next day. She would stare at me, I would stare at her even more. One day I got mad and went up to her to tell her off. I started to shout at her. I asked her ‘who do you think you are thinking you better than me?’ I called her stuck up, I was going to call her every name under heaven. Do you know what she said to me?”

Tio shook his head.

“She said she wished she was me. How nice I looked, how she would like to be my friend.

“Boy, I’m telling you, I felt so small. I was going to tell her this and tell her that, and cuss her, and she was so nice and wanted to be my friend. We still are friends. She went to England. She hates it there, mostly because of the climate and the fact she is used to life here. She writes to me occasionally. She never let me forget how troublesome I was to her. She teased me about it all the time because she knew how bad I felt about it.”

“So, what are you saying?”

“I’m saying it’s harder to dislike some people when you meet them. I’m saying they breathe the same air as us. They feel hungry like we do, they feel pain like us. They have to go to the toilet just like we do,” she laughed.

As Tio had said, he had not just asked anyone, he asked her. He knew she would give a considered, thoughtful answer. This was why he liked her.

“They don’t go to the same toilets in America,” he said, “They have one for white people, one for black.”

“But you are not going to America. You are going to England.”

He mulled over her words for a moment. He imagined she thought him foolish for asking philosophical questions when what was required was down to earth practicality.

There was a multitude of matters requiring attention. He must make arrangements for the care of his livestock and land. He had already initiated discussion with his brother Lipson, but the details must be hammered out. Then there were the references, the trip to Roseau to book and pay for the April journey, or perhaps send his friend Peter with the money. He would need far more warm clothes than he had, but there was no great call for them in Dominica so the shops did not stock many. If he bought them in Dominica they would be at a premium. Far better to buy them once he arrived – less packing, more readily available and above all, cheaper.

Tio could tell that something was on Clara’s mind. She was paying close attention to the floor again. No point in prompting her, he thought, she would come out with it when she was ready.

“You know, I think you will get on with the English too well.”

He knew what she was getting at, but played innocent.

“Too well? What do you mean?”

“I think you will find yourself an English woman for when you are lonely there. Doesn’t your brother have one?”

Tio picked another coconut from the pile and placed another coconut husk between his legs. He thought to reply but said nothing. Then he realised that in saying nothing he had replied.

“You know I will not be able to come to Roseau to see you off?”

“I know.”

“So, you will pass by and say goodbye before you leave?”

“Of course I…”

The first thing Tio was aware was an unfamiliar sound from the machete strike, then Clara’s shocked expression. Everything then blurred. In the briefest of moments, when his vision cleared, everything was covered in blood – his blood. The machete had almost severed his thumb.

Clara was shouting something. Was it to him, to someone else? Her mother, Evelyn, had arrived. Tio was prostrate by now. Once again, his vision failed.

Sometimes pain can be so intense that it no longer hurts. Evelyn, whose physical strength surprised the dazed and injured young man, tore a strip of fabric from somewhere, probably her own clothes. By the time he could feel the tourniquet tightening, he was drifting in and out of consciousness. Then nothing.

“I bring the Englishman,” announced Thomas indignantly, “he do nothing but shout at me all journey. I nearly throw him from the boat. I give him some rum. He sick all the time.”

“You know he does not like to travel. Anyway, he in pain. Thomas, you know this.”

Olivia’s instinctive defence of her younger brother was forged by many years of surrogate parenthood.

“He chop him fool hand with the machete before him go to England. Englishman already forget how to chop coconut. Now I bring him here and he can’t even go to England. I waste my time. He waste him money.”

No doubt many others at home were already disparagingly referring to emigrants as Englishmen. In fairness, it had been the same with Tio’s older brothers. Whether they had even embarked upon their journey was of no consequence. A joke perhaps, but a joke with an edge. Once departed, you were somehow less, not quite the real deal, no longer a bona fide islander.

“Thomas, you make me vex with you if you carry on so. He will go to England. He will rest here until he is okay. Has my father pay you?”

“Ton Pierre give me enough money and enough words.”

“And I will give you some more words. Do not be calling my brother an Englishman just because you don’t like him. He is a Mourillon. He is from Penville.”

“He was from Penville. The boy leave. He is an Englishman now.”

Olivia drew breath, ready to shout at Thomas but managed to restrain herself. Tio’s young travelling companion had delivered her brother from the north of the island safe and sound and for that she was grateful. At least now she could tend to him and hopefully, strengthen him sufficiently in preparation for the journey.

“You do not say who is he. His father say who. His mother say who.”

“Where is he mother?”

A flash of anger in Olivia’s eyes left the twenty-year-old Thomas in no uncertainty that it was time for him to beat a hasty retreat, no further conversation necessary.

Where indeed was his mother? Resting with all the saints was the answer, at least in part. The remaining part of the answer was that his mother was right there – she, Olivia, was had been his de facto mother from an early age.

Tio as a child had been small, wiry and beleaguered with asthma. As with all the Mourillon children, he had a temper and from time to time his manner could appear a little grave. The Mourillon boys were always fighting with the boys from Vielle Case and Thibaut, the neighbouring villages. Invariably they won.

One occasion upon which their father came home the worse for wear for drink, the children, wanting to avoid a beating, had hidden under their wooden house at Fon Bèlè. The young Tio saw this as yet another opportunity to frighten his younger brother Alphonse by making ghost noises as they lay there in the pitch dark, thinking it great fun to scare his younger brother witless. The fun ended abruptly when Alphonse reacted by shoving his large thumb from his large hand hard into Tio’s eye. From that moment on there were no more ghost noises, just whimpers of pain, just as now.

Olivia had to nurse her brother for a solid week after, just as it seemed she would have to tend to him now.

Back then, as Tio convalesced, he had overheard Olivia speculating amongst the womenfolk that the younger Mourillon boys would likely lack tenderness towards their wives because of the absence of their mother. Momentarily she caught a glimpse of the look of confusion on the young Tio’s face, but had been confident at the time that he was too young to understand the full meaning of what she was saying. That confidence soon waned, however, when he became withdrawn for several days after. From then on, she determined to put a bridle on her tongue, lest she upset her ever serious younger brother.

Serious as he may be, she would far rather suffer his frequent displays of ill humour, than see him sail across an ocean where she could be a mother to him no more.

But he would go, and she would cry for a while, but sooner or later she would reconcile herself to the thought that he was probably enjoying his adventures in a new and distant land.

For Tio, the three days prior to embarkation had been unspeakably fraught. It had started relatively straightforwardly with having to chase down his old head teacher, Clive Sorhaindo and then the police for references. The ever-precise Mr. Sorhaindo had provided his letter with the promptness and efficiency Tio would have expected. The police had also been punctual, supplying Tio’s reference two days earlier. He had drawn up a rudimentary document signing over his crops and livestock to his brother Lipson under instruction that should he sell any of the above, a proportion of the proceeds should be forwarded onto Tio. Lipson would tend the land in Tio’s stead.

All was relatively fine until the machete accident. Tio had sliced deeply into his left hand with a machete while stripping coconut husk. He had cut through to the bone. Everyone thought that he would lose his thumb completely. Evelyn Celestine’s prompt action had prevented that loss. Her makeshift patching managed to stem the blood loss - evidently being a seamstress could come in quite useful. No longer bleeding, he was then rushed to Portsmouth where he was further cleaned up and given some momentary rest.

None who had seen the severity of the cut, with the notable exception of Tio’s father, had thought he would be well enough to make the journey. Twenty-four hours before his scheduled departure Tio rallied. Everyone’s frantic efforts had paid off. He would make the journey.

The journey from nearby Portsmouth to the island’s capital, Roseau, was by boat. It was planned that he would stay with his eldest sister, Olivia, and her husband for one night as she was the only immediate member of his family living in Roseau.

As Tio stirred into consciousness, he was met with the comforting view of his sister’s face.

“Tio! Bondieux, bondieux! Sit up now. I expect you to pass by much earlier.”

Her tiny shack on the outskirts of Roseau had only two rooms worth mentioning. Small the dwelling may be, and modest too, but it bore the distinctive hallmark of the Mourillon family – tidiness.

“Brother, you look so pale. Come and sit up. I will go to the nurse and get you some new bandage.”

“Philomena has packed the bandage. Two bandage. In the case.”

Olivia removed the grubby dressing that smelled of fish and who knew what else, before painstakingly washing his hand with clean water and redressing it.

“There. No Mourillon boy going on the big important ship looking and smelling like a ruffian. You going on there looking tip top. And make sure Manuel carries your case when you getting on the ship.”

“Okay.”

“You must be hungry. Herminia who live next-door is making you some broth.”

Tio scanned his surroundings.

“Where is your husband?”

“He is not here now. You can stay on the bed in this room until the morning. It is no problem.”

“So why is he not here?”

Olivia had no appetite for discussing her husband’s whereabouts with her upstart brother. It was barely five minutes ago that she was tending him through asthma attacks and wiping his nose, or so it seemed.

“Little brother, just leave it alone.”

“Leave it alone?”

“Yes, leave it alone.”

“But why do you want me to leave it alone?”

“Tio, I am not getting into a big conversation with you about this. I am just telling you. Leave it alone.”

“Is he left you? Is he another woman?”

“He will be round here tomorrow for his meal. He is busy right now. He will be here.”

Olivia’s attempts at evasiveness left Tio to fill in the blanks. Up to now, he and everyone else in the family had been firmly under the impression that her move to Roseau had been an unmitigated success. After all, she had been the first to escape, if indeed she had escaped.

Years of duty and care, years of thwarted life opportunities, only to end up here – the most modest of dwellings, thought Tio, still in a state of torpor. She was here, though - this place where she could hear her neighbour’s conversations and her neighbours could hear hers, against the sound of the gentle lapping of the Caribbean Sea in the not too distant background.

Was this as far as any of the Mourillon children could go? No, he would go further, even if he had to die trying. Right now, that seemed a distinct possibility.

“Olivia? Hello.”

A woman’s voice could be heard outside.

“I see your brother pass by.”

“Yes. He cannot come and say hello. He chop his hand with a machete. He laying down now.”

“No? Is he okay?”

“He will be okay. He just need some rest.”

“I see he is not okay when he come in. I bring him some broth.”

“Ah, that is so kind.”

“And I bring him my husband coat from when he went to America. Does your brother have a coat? It will be cold in England.”

The conversation continued for several minutes, Tio only catching snippets. He heard mention of the broth and could by now smell it. The by now intense aroma only served to torture him further, given his now intense hunger.

Finally, the neighbour bade his sister farewell, after which Olivia emerged, food in hand, received eagerly by the patient.

“So, another brother goes to England. Soon I have no brothers left here.”

“It will be two years, maybe three. I will come back.”

“What does Papa Pierre say?”

“About what?”

“About you leaving?”

“He says bring him back his other friend when I come home.”

“You mean whiskey from Scotland?”

They laughed, but doing so brought on a surge of pain down the whole of Tio’s arm.

He grimaced.

“Why did this have to happen at a time like this?”

“Perhaps it is a good thing.”

“What? I nearly lose my hand. How is that a good thing?”

“Because you think about your hand, not about the journey.”

“Every single person thinks I cannot make journeys. Every single one. And yet I’ve been to Marie Galante, Guadeloupe, to Martinique.”

“Tio, those journeys are tiny. You are going to England. It takes weeks and weeks to get there. It is not like going to Guadeloupe.”

“I will be okay going there. Just the same as I was okay going everywhere else.”

His wilful amnesia was impressive, and it was quite apparent that no amount of disagreeing would convince him otherwise.

“You will not come back, I think.”

“Olivia, why you say that to me?”

“Because I think you will not come back.”

“But why? Gabriel and Everton have both said they will return.”

“But they are married.”

“And I am engaged to Clara.”

Olivia sucked her teeth.

“You should not have promised to marry Clara. It is not fair to her.”

“Is he because she’s older than me?”

“Booooy, that nothing to do with it.”

“What then?”

“Lickle brother, don’t be sounding so with me. You not too old for me to give you some blows. I used to wipe your nose when you were a small boy.”

Olivia drew breath, hesitated, then spoke.

“I do not think you love Clara, Tio.”

Tio’s expression was that of someone who had been struck.

“I have promised I will marry her. She has agreed to wait until I get back, so I am not treating her badly. Why do you say these things to me? Just because you are my sister, it does not mean you can just say what you like, you know.”

“Tio, calm down. It is not good for you to get vexed like this. I am sorry. Maybe I should have said nothing. It is your business, not mine.”

“But why do you say I do not love her?”

“I am saying nothing now. You just get upset.”

“Olivia, I am already upset. Why did you say what you have said?”

Another pause.

“Because in all the time we have been talking, I have not heard you say you love her. You have told me you have made a promise, you have told me her age does not matter, but you have not said you love her. And that is like telling me that you don’t”

Tio’s exasperated silence hung in the air for a while.

“Tio, once you get there, you will change. England will change you. Even if you don’t want it to. Do you think before our ancestor were brought here in chains they wake up one morning and say ‘I want to be a Dominican’?”

“Olivia, what are you talking about chains? No-one is making me go to England. I make the decision.”

“Brother, you do not understand what I am saying. I am saying that we are Dominican because we find ourselves here and we have to make a way here. Sometimes you become like where you are.”

“I am not going to England to stay, Olivia. This is my home. It always will be. I will always be Dominican.”

“A person cannot know the future, Tio. Fon Bèlè was my home. Now my home is in Roseau. You know, when I lived in Fon Bèlè, I thought a person who lived here in town were so much better than me. I do not think that now. I know better.”

“And do you know better about England?”

Olivia smiled wryly.

“I know you will leave, Tio. I think you left a long time ago. I left Fon Bèlè many years before I did leave there. I make all your meals, I clean and mend your clothes, I tend your wound, I look after you when your brother stick his thumb in your eye. I did all these things. I did not complain.”

Tio had never even given a moment’s thought to what it must have been like for any of his sisters. They were just there. As Olivia had said, she had not complained. But it was conspicuous how she had left at the first given opportunity. And Philomena, favourite of all his sisters, she had filled Olivia’s shoes immediately upon her departure. Surely, she would do the same, no doubt further afield than Roseau. Everyone, it seemed, was either leaving or plotting their departure.

“Your mind is across the water, Tio. It is right that you will go. I will be sad to see you leave because I may not see you again.”

“I will come back.”

“You cannot know that, brother. Only Papa Dieux can know such things. Come, eat some broth.”

Here, now, in Olivia’s home, Tio felt too ill for further debate. Bother him as it may that everyone seemed to believe he had behaved toward Clara in less than good faith, this debate would have to wait until another day. Everyone seemed to think they knew him better than he knew himself. Why? Were they saying the same things to Clara? It was infuriating.

For all of this, he knew Olivia was on his side, just as a mother would have been. She tended him, just as a mother would have tended him until confident that he had regained his strength sufficient to make the journey.

He felt a momentary surge of shame at having made a snap judgment about her circumstances, perhaps even having looked down on her without intending to.

Had his father perhaps given Olivia the same speech as he had given him when he was small – marking out a place in the world and tending it, no matter how small or humble? Why should his sister’s place automatically be inferior simply because she was his father’s daughter?

After all, this neighbour, whose face he had not seen, whose voice he had only ever heard, had shown kindness. She, never having met him, had fed him and given him a warm coat, once owned by her late husband. For all he knew, perhaps one day he may come to consider himself fortunate to fare as well as her.

Olivia had come away from Fon Bèlè, from Penville, from the rugged north, and ended up here in this tiny patch, with a seemingly absent husband and the most modest of dwellings. And yet for all that, she seemed happy, and the place – modest as it was – was hers. She had found her place in this world. It was time for Tio Mourillon to find his.

Background

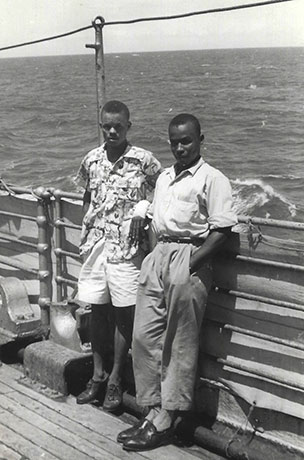

Machete AccidentThe photo to the right shows a young Max LeBlanc in shorts. Look closely and you will see that his left hand is bandaged. I initially understood that this was as a result of nearly severing his thumb while stripping a coconut, but I now know that not to be the case. It was as a result of my father and a man called Rosie Douglas sword fighting with machetes on the journed between Portsmouth and Roseau (what could possibly go wrong?!). LeavingChapters 4 and 5 cover two main themes - anticipation of the unknown, estrangement from their place of birth, even before the emigrants had left. Once they had left, many regarded the the departees no longer to be bona fide islanders. This was certainly my father's experience and many other's too. In the eyes of many, once he left, he was no longer fully Dominican, he was an Englishman. I know from my own experience that my father was averse to travelling long distances. Journeys to our place of vacation were usually tense, ill-humoured affairs, usually ending up with my mother being blamed for not navigating properly or something of the sort. Fear and ForebodingAnticipation and foreboding bear heavily upon Tio's mind in this chapter. He has already received letters from his brother in England. He knows he is not going to be welcomed with open arms, that the streets aren't paved with gold, that the climate is difficult, that he may be met with hostility and disrespect. It may make things uncomfortable, but he will be returning to Dominica anyway, so perhaps it's not of paramount importance. He sees that his sister has flown the coup with only limited success, given that she has only moved to Roseau, which bodes the question: is he setting out on a fool's errand? Does he have sufficient cold weather clothing for his destination? He ponders and re-evaluates. Perhaps his sister isn't doing so bad after all. As yet, his optimism remains intact. |

The anecdote that Clara recounts is actually from Jean Rhys's life. She had a staring match with a local girl who went on to berate her, only for Jean Rhys to tell her that she admired and wanted to be her.

The anecdote that Clara recounts is actually from Jean Rhys's life. She had a staring match with a local girl who went on to berate her, only for Jean Rhys to tell her that she admired and wanted to be her.